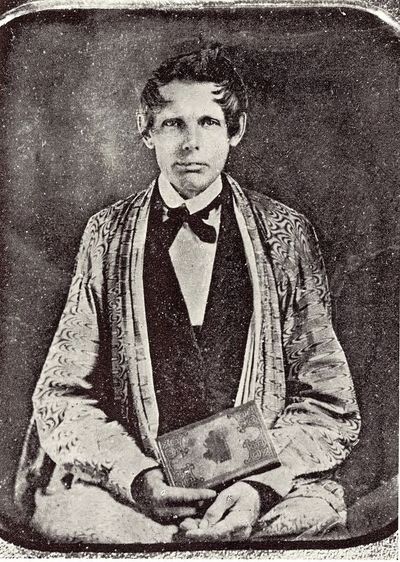

Sequoyah (ᏍᏏᏉᏯ) 1770-1843

Near the town of Tanasee, and not far from the almost mythical town of Chote lies Taskigi (Tuskeegee), home of Sequoyah. In this peaceful valley setting Wut-teh, the daughter of a Cherokee Chief married Nathaniel Gist, a Virginia fur trader. The warrior Sequoyah was born of this union in 1776.

Probably born handicapped, and thus the name Sequoyah (Sikwo-yi is Cherokee for "pig's foot"), Sequoyah fled Tennessee as a youth because of the encroachment of whites. He initially moved to Georgia, where he acquired skills working with silver. While in the state, a man who purchased one of his works suggested that he sign his work, like the white silversmiths had begun to do. Sequoyah considered the idea and since he did not know how to write he visited Charles Hicks, a wealthy farmer in the area who wrote English.

Hicks showed Sequoyah how to spell his name, writing the letters on a piece of paper. Sequoyah began to toy with the idea of a Cherokee writing system that year(1809).

View Complete History Resource Here:

Sequoyah

Sequoyah

Sequoyah Birthplace Museum

Sequoyah's Talking Leaves

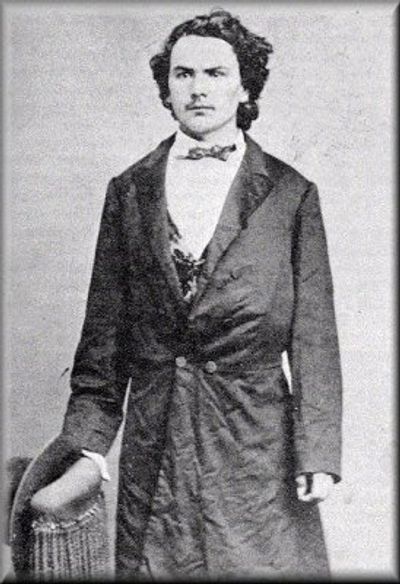

Samuel Austin Worcester ( 1798 - 1859 )

Missionary to the Cherokees, printer, prisoner, preacher, and translator. He was called "A-tse-nu-sti" which means "The Messenger". He brought to the people education, the ability to write their own language by using the symbols of Sequoyah, and he published a newspaper in both languages. Because his teachings helped the Indians he was arrested. Worcester vs Georgia is the case that upheld the Cherokee as an independent Nation but was ignored by President Jackson. Worchester moved to Oklahoma before the "Trail of Tears" and established the "Cherokee Phoenix" newspaper. He always worked for peace among the people, and his life-long goal of translating the Bible into Cherokee.

Other Web Links Referencing Samuel Austin Worchester

The Worcester Family

The A Missionary Case@: Worcester v. Georgia

Samuel Worcester, Pastor, Missionary to the Cherokee Indians

James Vann (c.1764 – 1809)

James Vann was an influential Cherokee leader, one of the triumvirate with Major Ridge and Charles R. Hicks, who led the Upper Towns of East Tennessee and North Georgia. He was the son of Wah-Li Vann (Cherokee), and Scottish trader Joseph John Vann. He was born into his mother's Wild Potato clan (also called Blind Savannah clan) As a young man, he helped lead the John Watts' 1793 offensive against the Holston River colonial settlements. They originally planned an attack against White's Fort, then capital of the Southwest Territory (as Tennessee was known). As the war party was traveling to the destination, Vann argued they should kill only men, against Doublehead's call to kill all the settlers.

Not long after this, the war party of more than 1,000 Cherokee and Muscogee came upon a small settlement called Cavett's Station. Bob Benge, a leading warrior, negotiated the settlers' surrender, saying no captives would be harmed. But, Doublehead's group and his Muscogee Creek allies attacked and began killing the captives, over the pleas of Benge and the others. Vann managed to grab one small boy and pull him onto his saddle, only to have Doublehead smash the boy's skull with an axe. Another warrior saved another young boy, handing him to Vann, who put the boy behind him on his horse. Later he gave him to three of the Muscogee for safe-keeping; a few days later, a Muscogee chief killed and scalped the boy. Vann called Doublehead "Babykiller" for the remainder of his life

Chief Major Ridge 1771-1839

President Andrew Jackson told the Ridge family he wanted the Cherokees out of Georgia no matter what, even though the Georgia Supreme Court said they could stay. Cherokee Chief Major Ridge was a patriotic man. He did what he thought was best for the Cherokee people, therefore, he, son John Ridge, nephews Elias Boudinot (changed his name from "Buck" Watie) and Stand Watie (Major Ridge's brother was David Oo-Watie), and several other Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota, which traded Indian lands in Georgia for acreage in Arkansas and Oklahoma. The treaty was signed on December 29, 1835, in Elias Boudinot's home in New Echota, Georgia. New Echota was the Cherokee capital between 1825-1839.

Major Ridge wrote the Cherokee law that called for treason if an Indian sold his land. After signing the treaty, he said "I have signed my death warrant." Five months later, Major Ridge also said "I expect to die for it."

The Ridge/Watie Family and the treaty party moved west comfortably under the protection of the U.S. Government. The rest of the Cherokee people were expected to do the same.

The Cherokee people were upset because the treaty was not voted on by the majority. They also did not want to leave Georgia. Principle Chief John Ross stalled and asked the government for more money and provisions. Jackson did not like John Ross. Jackson called him a "villain," "greedy," and a "half-breed" who cared nothing for the moral or material interests of his people. `The treaty had a final removal date and that forced the rest of the Cherokees to leave. The treaty led to the infamous "Trail of Tears." Four thousand out of sixteen thousand died on the journey including Mrs. Ross.

After the Cherokees were relocated to Oklahoma, a band of Cherokees assassinated Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot on June 22, 1839. A Choctaw, who saw Elias assassinated, rode Samuel Worcester's horse "Comet" to warn Stand Watie. Stand escaped on the horse. For years, Cherokees were divided by those that followed the Ridge/Treaty party and those that followed Principle Chief John Ross. Many believed that John Ross had them assassinated but it was never proven. The assassins were never brought to trial. When John Ross heard of Major Ridge's fate, he said "Once I saved Ridge at Red Clay, and would have done so again had I known of the plot." The feud went on for years, even after Oklahoma became a state in 1907. John's own brother Andrew Ross signed the treaty but was not assassinated. In fact, the removal was an idea of Andrew's. William Shorey Coody, a nephew of John Ross, was also affiliated with the treaty party.

President Jackson knew that the Cherokee would survive and endure. He was right. Today, there are three governmental bodies - Cherokee Nation West, Cherokee Nation East, and the Original Cherokee Community of Oklahoma. That's more than you can say about the Yemassee, Mohegans, Narragansetts, Pequots, Delawares, and any number of other dead tribes.

The Civil War did as much damage to the Cherokees as did the "Trail of Tears." Eighty percent of the Cherokee people wanted to fight for the Confederates. John Ross was a northern sympathizer. Cherokees fought against each other. Past historians have always had unkind words for the Ridge Family and treaty party. Historians are now saying that the treaty may have saved the Cherokee people from total destruction. If interested in learning more about the Cherokee Nation, read "Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People," by Thurman Wilkins, University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

Cherokee Chief Major Ridge (1771-1839) is buried at Polson Ridge-Watie Cemetery in OK, near Southwest City, Missouri. John Ridge (1802-1839), is buried next to him. Major Ridge's home in Rome, Georgia, is the Chieftains Museum/Major Ridge Home, a national Historic Landmark and a certified historic and interpretive site on the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. His Indian name is KA-NUN-TLA-CLA-GEH, meaning "The Lion Who Walks on the Mountain Top." The white man shortened it to Ridge. General Andrew Jackson of the United States Army gave Ridge his name "Major" after Ridge led a force of Cherokees in the Battle of the Horseshoe against the Creeks. Indians had previously used no surnames. Major Ridge's and John Ridge's portraits are in the Smithsonian archives.

Other Web Links Referencing Major Ridge

Major Ridge-Watie

Major Ridge or The Ridge

Chieftains Museum

Joseph Vann 1798-1854

Joseph Vann, known as "Rich Joe", was a wealthy Cherokee whose large plantation at Springplace, Georgia was worked by hundreds of African slaves. He was a friend of Chief John Ross and was a frequent delegate to Washington DC on tribal business. He served as Ross's assistant principal chief at the beginning of the American Civil War.

The Vann House at Springplace, Georgia was built by James Vann. James Vann was killed in Forsyth County, Georgia, and buried in same. He was buried next to Buffingtons Tavern, which he owned, on the Old Federal Road. The Tavern has now been moved to the Cumming City Park.

The house was then inherited by his son Joseph "Rich Joe" Vann. In 1833, his mansion was taken by Col. William Bishop of the Georgia Guard and turned into Georgia Guard headquarters. At the time of removal, Rich Joe's property valuation showed him as the second richest man in the Nation.

Other Web Links Referencing Joseph Vann

Chief John Joseph Vann & Marker

Chief Vann House State Historical Marker

Joseph Vann

Elias Boudinot [ᎦᎴᎩᎾ ᎤᏩᏘ] 1802-1839

Elias Boudinot was born Gul-la-gee-nah "Buck Deer" Watie, brother of Stand Watie, in Georgia in 1802. His benefactor at the foreign mission school in Cornwall, CT, Elias Boudinot, was so impressed with the young Cherokee that he gave him his name.

Although active in Cherokee government, Boudinot is best known for signing the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, which traded Cherokee ancestral homelands in the east for lands west of the Mississippi River. Boudinot and two other members of the Treaty Party, Major Ridge and John Ridge, were killed on June 22, 1839, for signing the treaty.

Boudinot was the first editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Cherokee newspaper, from 1828 to 1832. We wrote editorials denouncing the removal policies until he began to believe that Cherokees would best prosper away from the white man in Indian Territory.

Other Web Links Referencing Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot, Editor of the Cherokee Phoenix

Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot, Cherokee Letters and Other Papers Relating to Cherokee Affairs:

The Cherokee Phoenix

Mission Statement by Elias Boudinot, founding editor

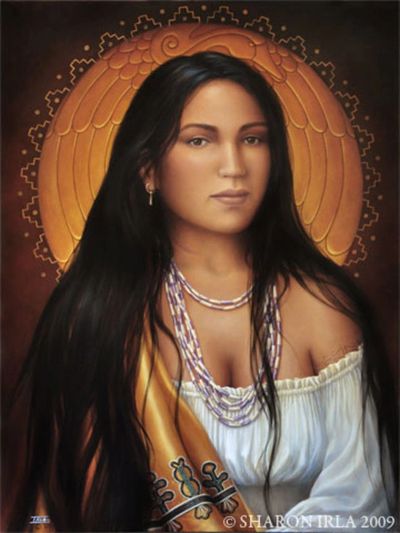

NANCY WARD ᎾᏅᏰᎯ 1738-1824

According to legend, Nancy Ward had accompanied her warrior husband, King Fisher, to the battle of Taliwa to drive the Creeks out of northern Georgia. When he was killed, she picked up his gun and joined the fighting. It is said her bravery caused a turning point in the battle for the outnumbered Cherokees.

Upon returning to her tribe, she was given the title of Ghighau or Most Honored Woman which was considered a lifetime distinction bestowed for valorous merit. Still only a teenager, she sat with the Peace Chief and War chief in the "holy area" near the ceremonial fire during the State Council meetings. She also was the last Chief Woman of the Cherokee Female Council. She died in 1822 as is buried near Benton, TN.

Profiles of Martin's Station (1775): "Nancy Ward"

General Stand Watie ᏕᎦᏔᎦ 1806-1871

Born at Oothcaloga in the Cherokee Nation, Georgia (near present day Rome, Georgia) on December 12, 1806, Stand Watie's Cherokee name was De-ga-ta-ga, or "he stands." He also was known as Isaac S. Watie. He attended Moravian Mission School at Springplace Georgia, and served as a clerk of the Cherokee Supreme Court and Speaker of the Cherokee National Council prior to removal.

As a member of the Ridge-Watie-boundinot faction of the Cherokee Nation, Watie supported removal to the Cherokee Nation, West, and signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, in defiance of Principal Chief John Ross and the majority of the Cherokees. Watie moved to the Cherokee Nation, West (present-day Oklahoma), in 1837 and settled at Honey Creek. Following the murders of his uncle Major Ridge, cousin John Ridge, and brother Elias Boundinot (Buck Watie) in 1839, and his brother Thomas Watie in 1845, Stand Watie assumed the leadership of the Ridge-Watie-Boundinot faction and was involved in a long-running blood feud with the followers of John Ross. He also was a leader of the Knights of the Golden Circle, which bitterly opposed abolitionism.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Watie quickly joined the Southern cause. He was commissioned a colonel on July 12, 1861, and raised a regiment of Cherokees for service with the Confederate army. Later, when Chief John Ross signed an alliance with the South, Watie's men were organized as the Cherokee Regiment of Mounted Rifles. After Ross fled Indian Territory, Watie was elected principal chief of the Confederate Cherokees in August 1862.

A portion of Watie's command saw action at Oak Hills (August 10, 1861) in a battle that assured the South's hold on Indian Territory and made Watie a Confederate military hero. Afterward, Watie helped drive the pro-Northern Indians out of Indian Territory, and following the Battle of Chustenahlah (December 26, 1861) he commanded the pursuit of hte fleeing Federals, led by Opothleyahola, and drove them into exile in Kansas. Although Watie's men were exempt from service outside Indian Territory, he led his troops into Arkansas in the spring of 1861 to stem a Federal invasion of the region. Joining with Maj. GEn. Earl Van Dorn's command, Watie took part in the bAttle of Elkhorn Tavern (March 5-6, 1861). On the first day of fighting, the Southern Cherokees, which were on the left flank of the Confederate line, captured a battery of Union artillery before being forced to abandon it. Following the Federal victory, Watie's command screened the southern withdrawal.

Watie, or troops in his command, participated in eighteen battles and major skirmishes with Federal troop during the Civil War, including Cowskin Prairie (April 1862), Old Fort Wayne (October 1862), Webber's Falls (April 1863), Fort Gibson (May 1863), Cabin Creek (July 1863), and Gunter's Prairie (August 1864). In addition, his men were engaged in a multitude of smaller skirmishes and meeting engagements in Indian Territory and neighboring states. Because of his wide-ranging raids behind Union lines, Watie tied down thousands of Federal troops that were badly needed in the East.

Watie's two greatest victories were the capture of the federal steam boat J.R. Williams on June 15, 1864, and the seizure of $1.5 million worth of supplies in a federal wagon supply train a the Second battle of Cabin Creek on September 19, 1864. Watie was promoted to brigadier general on May 6, 1864, and given command of the first Indian Brigade. He was the only Indian to achieve the rank of general in the Civil War. Watie surrendered on June 23, 1865, the last Confederate general to lay down his arms.

After the war, Watie served as a member of the Southern Cherokee delegation during the negotiation of the Cherokee Reconstruction Treaty of 1866. He then abandoned public life and returned to his old home along Honey Creek. He died on September 9, 1871.

Source: Macmillan Information Now Encyclopedia, "The Confederacy", article by Kenny A. Franks

Cherokee Almanac: Stand Watie's Ceasefire

Saladin Ridge Watie

Saladin Ridge Watie, son of Stand Watie, enlisted in the Confederate service at fifteen and rose to the rank of captain in his father's Confederate Indian brigade. He was cited for exceptional bravery by Gen. D.H. Cooper at the 1864 attack on Union forces at Fort Smith AR. He served on the Southern Cherokee delegation to Washington in 1866. Saladin died of a sudden illness at Webber's Falls in 1868 -- only 21 years old.

Other Web Links Referencing Saladin Ridge Watie

Indian Territory Confederate Heroes

Brigadier General

American Indian Confederate Heritage

John Ross

Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1828–1866

John Ross, a man with the legend touch, walked tall upon the earth and cast a long shadow. He set a precedent in democratic political history that will never be broken. By free ballot, he was elected to ten successive terms of four years each as principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. He died in office as chief executive of a government fashioned after that of the United States of America.

Intellectually, he was the greatest chief in the history of the Cherokee people.

In his youth he knew Jefferson, spent most of his prime negotiating with Jackson, came face to face with Lincoln. In Washington, he was known as the Indian Prince. Yet, for all his impressive contacts, he was a man of simple and friendly habit, his home ever open to visitors of all walks of life, including John Howard Payne who once shared a jail cell with him and where Payne got the idea for the song, Home, Sweet Home.

John Ross stood so high in the eyes of his people that they called him Guwisguwi, the name of a rare migratory bird of large size and white or grayish plumage that had one time appeared at long intervals in the old Cherokee country. He Was only one-eighth Cherokee and seven-eighths Scot. He was as much a Scotsman as his great opponent, Andrew Jackson, and fought just as tenaciously. But he was forever Cherokee-minded.

Scion of a prominent trading family that had settled before the American Revolution at what is now Rossville, Georgia, just across the line from Chattanooga, Tennessee, he was born October 3, 1790.

He was educated at a white man's school at Kingston, Tennessee, and began his public career at the age of nineteen when he was entrusted by Indian Agent Return Meigs with an important mission to the Arkansas Cherokee in 1809. He was a veteran of the Creek campaign in which the Cherokee established the reputation of their archenemy-to-be Jackson instead of shooting him down as some Cherokee veterans later wished they had.

Ross Fought alongside Jackson and Sam Houston and Davy Crockett in the was of 1812, and at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, in a daring act of bravery, he swam the river to capture the Creek's canoes which were then used to effect an attack upon the enemy's fort.

Ross, more than anyone else, was responsible for remodeling the Cherokee tribal government into a miniature republic with a written constitution.

This republican form of government came into being in 1820. Under the arrangement, the nation was divided into eight districts. Each was entitled to send four representatives to the Cherokee national legislature, which met at New Echota, the capital, near the present Calhoun, Georgia. The legislature consisted of an upper and a lower house. The Cherokee referred to them, respectively, as the national committee and the national council.

The principle official in the government was the president of the national council. Because he had shown great leadership, the office fell to John Ross.

Meanwhile, Sequoyah had invented his alphabet and overnight the Cherokee became a literate race. This led, in 1828, to the adoption of a constitution, development of a system of industries and home education, and establishment of a national press.

The constitution was predicated on the Cherokee assumed sovereignty and independence as one of the district nations of the earth. The bold step drew the immediate wrath of authorities and people of Georgia and set off the first argument for state's rights, with Georgia asking the United States government what it proposed to do about the "erection of a separate government within the limits of a sovereign state."

As the battle raged, Ross dreamed that one day a new star would be added to the flag of the United States and that it would stand for a state the like of which had not yet been received into the Union - an Indian state, the State of Cherokee. But this was not to be, and John Ross found himself spending most of his time in Washington fighting the removal of the Cherokee to new homes in the west. His knowledge of the writings of Jefferson enabled the Cherokee to present memorials of dignity and moving appeal to Congress. He almost won the fight. He lost it by one vote. Throughout the long and hard battle, Ross' people trusted him, sometimes almost blindly. Even when the Cherokee were finally removed to what is now Oklahoma in 1838, he continued to fight.

After their arrival in the Indian Territory, Ross was chosen chief of the united Cherokee Nation and held that office until his death in Washington on August 1, 1866 at the age of 76. Upon learning of his death, the Cherokee Nation passed a memorial resolution that read in part:

"He never faltered in supporting what he believed to be right, but clung to it with a steadiness of purpose which alone could have sprung from the clearest convictions of rectitude. He never sacrificed the interests of is nation to expediency. He never lost sight of the welfare of the people. For them he labored daily for a long life, and upon them he bestowed his last expressed thoughts."

A friend of law, he obeyed it; a friend of education, he faithfully encouraged schools throughout the country; and spent liberally his means in conferring it upon others. Given to hospitality, none ever hungered around his door. A professor of the Christian religion, he practiced its percepts. His works are inseparable from the history of the Cherokee people for nearly a half a century, while his examples of the daily walks of life will linger in the future and whisper words of hope, temperance, and charity in the years of posterity."

Resolutions were also passed for bringing his body from Washington at the expense of the Cherokee Nation as providing for suitable funeral rites and burial, in order "that his remains should rest among those he had so long served." He was buried at Park Hill, Oklahoma, his home.

Other Web Links Referencing Chief John Ross

John Ross, leader of the Cherokee

Cherokee Chief John Ross

Chief John Ross

"Our Hearts are Sickened": Letter from Chief John

Chief John Ross of the Cherokee Nation